A Churchill Fellowship Report released this week calls for more creative engagement in the GB energy system, as expectations for domestic demand flexibility continue to rise.

The report, ‘Powering Participation: Exploring how creative engagement can unlock domestic demand side response’ is the result of several months research by Tim Crook, Head of demand and flexibility at Regen, funded by the Churchill Fellowship asking: What motivates people to change behaviour?

The change in this case is participating in Demand Side Response (DSR). Many people will have no idea what that is or why it’s important. And that’s precisely the problem.

To achieve Net Zero carbon emissions in Great Britain, there must be much greater flexibility in when and how electricity is used, homes included, to better match the varying levels of renewable energy generation and to accommodate the increasing numbers of electric vehicles and heat pumps. That flexibility will, in part, come from the citizens of Great Britain having the means, motivation and opportunity to shift their electricity demand around.

DSR is a way of describing how reducing or shifting MW of demand around the day can have a huge impact on running the electricity network. It makes sense: reducing demand by a MW somewhere means that a MW of supply does not have to be found to match and routed through the network. And let’s not forget: the network can get full.

But to access that flexibility in homes, we need to engage people. Even if we could automate all of this flexibility, we would still need to engage the population with how it works as they are the ones paying for it after all and would need to understand the implications of automation.

Energy literacy is low in Great Britain. Many people are confused by their energy bills and are not clear what a kWh is, let alone how moving their demand around might directly help mitigate change. This is why existing DSR schemes in GB, across suppliers, focus on money savings. It’s an easier sell.

The example that sparked the research was the electricity system event of 6th September 2022 in California.

The day after Sacramento hit a record high of 47⁰C, electricity demand in California hit an all-time high of 52 MW. The electricity system operator, (California Independent System Operator, CAISO) had been issuing alerts all week appealing to customers to reduce their energy demands. CAISO was running out of tools to manage the demand and on the afternoon of the 6th issued its highest alert, Level 3, signaling that rolling power outages might be implemented if demand didn’t drop.

What happened next?

Shortly after the Level 3 alert, the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES) issued a mobile phone alert. Everyone who received that message was asked to turn off or reduce nonessential power if health allowed.

Within minutes, demand had dropped by 1.2MW. Rolling outages were avoided.

Thousands of people had taken action because they knew it mattered and had been asked for help. They weren’t paid. There were probably inconvenienced by taking part, but they did it anyway.

Responding to emergency alerts is not a desirable, or long-term way of managing a system. Asking for that sort of response in that way must remain a last resort. But it demonstrated an important lesson:

How you ask for action matters.

Here in Great Britain, we also have several tools to balance electricity supply and demand and DSR is one of them, but until recently this had been limited to industrial and commercial customers.

The GB system operator, NESO, is encouraging electricity suppliers to get householders involved in providing this flexibility, but how do you encourage citizens of a country to think about their energy use and shift it around? The obvious answer is just allow economics to find the right value for both participant and system. But this approach masks a more knotty problem:

Why are some narratives and ‘asks’ more compelling than others? Could changing the narrative around energy use help us manage the system and make customers feel more empowered in addressing climate change?

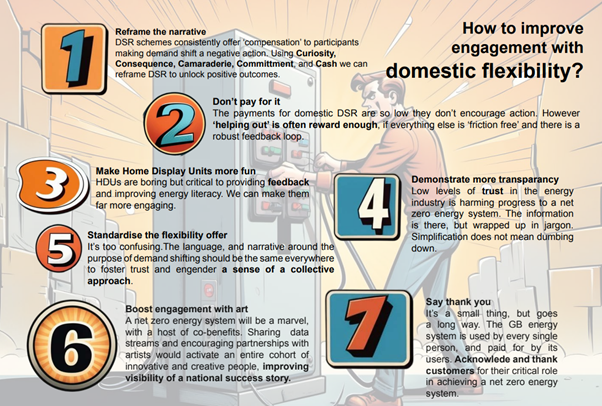

The report presents seven key findings that could improve engagement with the energy system and DSR Specifically:

Why are these seven findings so critical?

These findings recognize that there are many motivators for being interested in energy, but they must be used in combination to be most effective. Currently, most DSR schemes use just a single motivator, money, to encourage participation, offering moderate to low levels of ‘compensation’ for users to shift their demand. But this narrative sets up three challenges from the get-go:

- It implies that something is being lost, and must be compensated for

- A low value for flex implies it is unimportant

- Because values are low, it emphasises that unless you can afford high flex tech like heat pumps and EV’s in the first place, there’s no point in taking part.

The narrative often being used by suppliers in GB is about saving money, when it should be about helping the nation decarbonize and make better use of its renewables.

A potentially far more powerful approach would be to stop offering low levels of financial reward to individual participants and instead provide detailed feedback about what their DSR achieved.

Rewards have a part to play, but given they are so low for any one participant, those rewards would be far more powerful if converted to something local communities care about, like fundraising for good causes, helping pay for more police, or the knowledge that their local gas peaking plant was not switched on saving X tonnes of CO2.

The point is, DSR could actually be a hugely valuable example of how individual efforts, no matter how small, are contributing to a greater good and direct action on climate change. The critical element is to provide rapid, customized feedback to participants in engaging, creative ways that can be fun rather than depressing: e.g. a message that reads “ Your street avoided producing 20 transit vans full of carbon last night, and you helped by contributing a bathtubs worth of that. Thank you – it all counts. By the way, it’s going to be windy tomorrow lunchtime, so use power then if you can. GB is on track for electricity to be 80% renewable this year.”

That already seems more motivating than an email months after the fact saying the participant had saved £1.

But reframing the narrative won’t work on it’s own.

Motivators have to be used in combination to be most effective. This is where using novelty, humour, or straight up attractiveness comes in. For example, why not use the data already generated by the energy system to create public works of art that show current carbon intensity of the grid, or interactive maps in supermarkets showing where the most abundant renewable energy generation will be in 24 hrs.

Motivators have to be used in combination to be most effective. This is where using novelty, humour, or straight up attractiveness comes in. For example, why not use the data already generated by the energy system to create public works of art that show current carbon intensity of the grid, or interactive maps in supermarkets showing where the most abundant renewable energy generation will be in 24 hrs.Achieving clean power 2030 will need a huge increase in investment from the public, replacing gas boilers with heat pumps and petrol/diesel cars with EVs. This investment will only happen if there is far greater engagement from the public in their energy system fueling a willingness to choose differently. That has to encompass more than just ‘savings’. Creative thinking could transform not just the system, but how we think about our renewable energy powered future.

These quotes from the Centre for Sustainable Energy review on 2022/23 DFS trial for National Grid ESO (now NESO) perhaps best sum it up:

“Personally I wouldn’t waste my time as it hardly made any difference, I committed so much into completely switching everything off for an hour for a measly £1.30”

“They [rewards] were alright but if I wasn’t motivated in another way, I wouldn’t have found them that inspiring.

“It sort of came and went and nobody seemed to say anything, and it wasn’t generating the same sort of traffic’ [as Clap for Carers].

“It would be good to make more of a fuss about it and it would be good to hear that it did have a positive impact”

By reframing how we think about DSR, what it is for and why people should care, we can create a future-positive view of net zero, one that taps into much more powerful motivators than just money. Participating won’t just be good for the system, it will feel good for us too.