Despite decades of availability and proven savings, compressed air heat recovery remains a rarity in UK factories. Is cost the barrier, or is it simply a case of misplaced concerns around complexity and other priorities asks Michael Pingram, Product Specialist, Atlas Copco Compressors UK

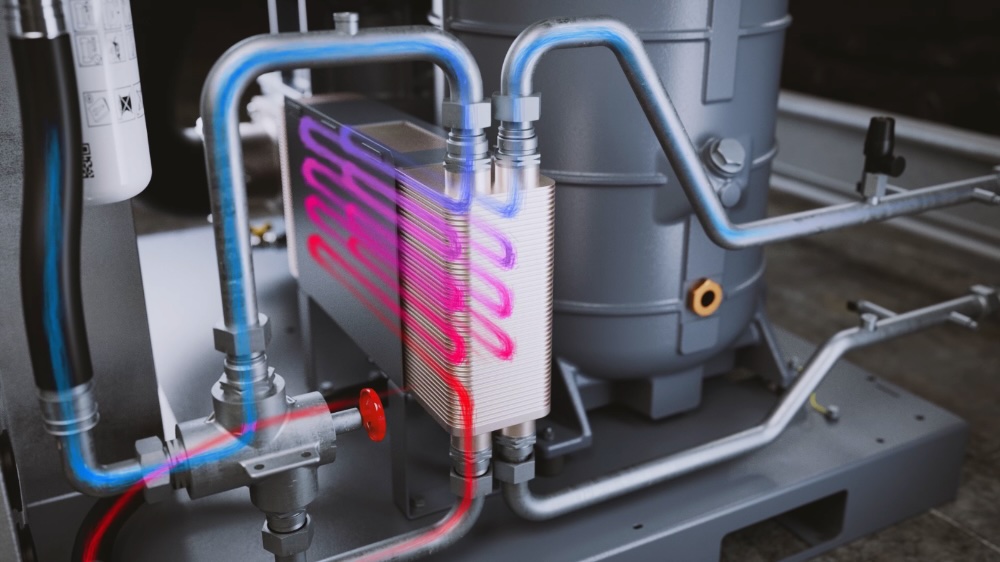

Compressed air is ubiquitous in modern manufacturing. From food and drink to pharmaceuticals, automotive to packaging, few industrial processes run without it. But it is also one of the most energy-intensive utilities. As much as 90% of the energy consumed by a compressor is converted into heat; heat that is usually vented away into the atmosphere.

For decades, that wasted energy has been an open secret. The technology to recover it is not exotic. In fact, it is relatively simple: systems that capture the heat and repurpose it as hot water or warm air for use elsewhere in the plant. The energy is already being generated as a by-product of compression; the real choice is between harnessing it or wasting it.

This is the paradox of compressed air heat recovery. At a time when energy prices are volatile and sustainability commitments are under scrutiny, a proven means of reducing costs and emissions is being overlooked. The reasons for this lie less in technology than in perception.

Why aren’t more manufacturers using it?

Recovering heat from compressors is not new. Water-cooled machines have long lent themselves to recovery systems, while air-cooled models can be modified with ductwork to redirect hot air into working spaces. Over the past two decades, manufacturers have refined these solutions, making them more efficient, compact and compatible with modern plant control systems.

Elsewhere in Europe, uptake has been stronger. Projects in Scandinavia, Germany and the Benelux countries have shown how recovered heat can be integrated with district heating networks or factory processes. In the UK, however, adoption has lagged behind. There are standout examples – Greiner Packaging’s Northern Ireland plant, for instance, which pipes waste heat to a neighbouring school – but they remain the exception.

Uncertainty lies at the heart of the issue. Many factory managers are simply not sure whether recovered heat can be put to good use on their sites. Will it integrate with existing boiler systems? Will it deliver enough hot water to make a difference? How disruptive will the installation be?

The hesitation extends to economics. Although payback periods of three to five years are common, potential adopters worry about upfront costs and whether their operations will run long enough to see the return. For manufacturers used to short planning horizons – often no more than five years – such investments can appear risky.

Another factor is confidence and familiarity. While the underlying technology is well established, many compressed-air engineers and specifiers have limited experience in linking compressor systems with hot-water circuits or existing boiler infrastructure. The design principles are different, and the training available to bridge these disciplines has historically been limited. As a result, heat recovery can feel like unfamiliar territory for some sites. The answer lies not in complexity, but in collaboration – drawing on partners who understand both compressed-air performance and heat-recovery integration from the outset.

Policy also plays a part. While government schemes once offered allowances and grants for energy recovery, today there is little top-down encouragement. The Energy Savings Opportunity Scheme requires large businesses to audit their energy use, but it stops short of mandating action. Without regulatory pressure or incentives, many organisations identify opportunities only to leave them unfulfilled.

Lessons from the factory floor

Perception is another barrier. To many plant managers, heat recovery seems like a ‘dark art’ – complicated, expensive or disruptive. In reality, the fundamentals are straightforward: capturing heat from the compressor’s cooling system or redirecting warm air through ductwork. However, larger multi-compressor installations can introduce additional design and control considerations, particularly where lead/lag or back-up systems are in place. That complexity is manageable when specialist partners are involved, but it does underline the need for early design input and site-specific planning. Once decision-makers see that these challenges can be engineered out with the right expertise, the objections often melt away.

One UK food producer offers a telling example. A leading dessert manufacturer recently invested in new oil-free compressors to safeguard production and improve energy efficiency. The project delivered immediate electricity savings of £117,000 a year. Crucially, by integrating heat recovery units, the company also repurposed the waste heat from its compressors to support other processes such as boiler pre-feed and wash-down water.

The additional savings from heat recovery reduced the project’s payback period to just three and a half years. For a sector under pressure to cut costs while maintaining stringent hygiene standards, the ability to extract extra value from an existing utility made the investment even more attractive.

This case demonstrates that heat recovery is not an add-on gimmick but a core part of a modern compressed air strategy. If a desserts plant can turn waste heat into a resource, other sectors can do the same.

From mystery to mainstream

The frustrating reality is that compressed air heat recovery should by now be standard practice. Every plant that uses hot water or heating could, in theory, benefit. The technology is mature, the payback is proven, and the environmental benefits are clear. Yet inertia persists.

Some of this is down to awareness. Some of it is down to risk aversion. And in many cases, it comes down to investment decisions. Even when the benefits are recognised, the additional cost of designing and installing a heat-recovery system may be deferred in favour of more immediate production priorities. In the daily pressure to keep production running, efficiency measures can feel like a luxury. But ignoring the opportunity comes at a cost. Wasted heat is wasted money, and in the current energy climate, that is harder than ever to justify.

What will it take to shift the dial? Part of the answer lies in stronger collaboration and confidence. Working with specialist partners who understand both compressed-air and hot-water systems can remove much of the perceived complexity and risk. These partners can provide return-on-investment assessments, turn-key project management and ongoing after-sales support – giving manufacturers the reassurance they need to act.

Training is equally vital. Sales and specification teams who understand the principles of heat recovery can raise it earlier in design discussions, while engineers equipped to maintain integrated systems can help end users see that it’s a realistic, low-risk route to energy savings. Engaging consultants and contractors at the outset can also ensure heat recovery is considered during the earliest stages of a project rather than bolted on later.

With these enablers in place, manufacturers can begin to view heat recovery not as a peripheral option but as a mainstream efficiency measure – as integral as variable speed drives or LED lighting.

Compressed-air heat recovery is not a new idea. It is not unproven, nor is it prohibitively complex. It is, however, misunderstood. The mystification surrounding it has allowed a valuable source of savings to be overlooked.

Compressed-air heat recovery is not a new idea. It is not unproven, nor is it prohibitively complex. It is, however, misunderstood. The mystification surrounding it has allowed a valuable source of savings to be overlooked.

At a moment when UK manufacturing is under intense pressure to cut costs, reduce emissions and strengthen resilience, this is a missed opportunity. The paradox of wasted heat must end. By demystifying the technology, clarifying the economics and building the right partnerships, the industry can unlock an efficiency measure hiding in plain sight.

The question is not whether compressed-air heat recovery works. It is why so few are using it. And in that, the real mystery lies.