Post subsidies, solar developers have to double down on costs and seek other revenue streams to make project economics stack up. Some are now looking at co-locating storage as a means of increasing revenue streams and returns, others are cutting costs by reducing system resilience.

However, there are ways of shaving cost and optimising solar returns without increasing project risk that could make projects more viable – with or without storage.

These may sound obvious sales pitches. Yet the ability to reduce performance risk can lower cost of capital. Providing banks with medium-term visibility on revenues, particularly where storage is concerned, could determine the fine margins between success and failure in a post-subsidy world.

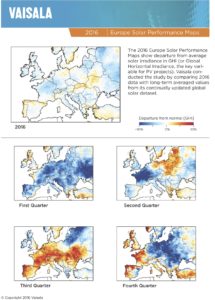

Better weather data

Gwendalyn Bender is head of solar services at Finnish weather measurement company Vaisala. She believes as solar projects pursue merchant revenue streams as opposed to subsidies, “the willingness [of project backers] to absorb fluctuations that you can actually predict will diminish”.

She says Vaisala’s satellite data enables it to build a 20-year weather data set for solar, based on actual observations and imagery, with resource uncertainty of 4-5%. Factoring in variables – such as equipment performance, degradation, some tolerance around the ability to model actual project conditions etc – translates to an energy uncertainty, for solar operators/developers, of 7-9% over the asset life, says Bender.

She believes that the solar sector will need to become more efficient and attuned to stronger risk management principles now that subsidies have been turned off.

“When you have a high subsidy you can absorb an uncertainty, or an underperformance. But [in a post-subsidy world], if 2% is your revenue, that has a different impact,” says Bender. “So there is more we can do to improve our project practices.”

Bender says accuracy of whether data “is one of the largest components of energy uncertainty”, in renewables projects. Yet while subsidies existed, “most of the market was probably built on freely available public data of a fairly low to poor resolution on typical averages”, she says.

“That’s great for understanding average conditions, but you have no insight into the variability at that site. So then people get surprises. They take all of the hit of low resource periods and can’t take advantage of high resource periods.

“That is certainly something to keep in mind over next couple of years,” adds Bender, “because you are likely looking at a market that does not understand the potential variability that exists.”

Solar and storage data

Better long-term weather data will be complemented by short-term accuracy once batteries are collocated, says Bender.

“With any sort of dispatchability, knowing what is going to happen in the next couple of hours or days is extremely valuable,” she says.

“I have had several conversations with banks regarding storage. They see it coming, that the tide is turning, but they are also inherently nervous. Solar people are inherently optimistic. They are coming in with expectations of how they are going to manage [storage] and how it is going to work, without necessarily having tested it,” Bender continues.

“Banks are trying to get up to speed as fast as everyone. But anything you can do to prove that you have the data to operate more efficiently, to mitigate risk … could go a long way towards giving them more confidence.”

Hedging the new subsidy?

The company insures against lost revenue as well as physical assets and has recently sold its first weather transfer risk (WTR) packages in the UK.

Insuring against loss of revenues is a “self-funding proposition”, says McLachlan, because it “enables developers to get a lower interest rate on debt”.

The product can work as a swap, in a similar way to contracts for difference.

“So if it is a sunny year, and you are up, we will take some of your upside and vice versa,” says McLachlan. “Banks like it because it provides certainty. They just want guarantees their investment will perform at a set rate.”

Technical failure

McLachlan also thinks that tighter margins post-subsidies mean developers are looking closely at project costs, and the contingency measures they build in.

The result is “a lot more risk with regard to single point failures”, says McLachlan.

“As margins are squeezed, they are building projects to a price. From an insurance perspective, they are looking to transfer the risk back into the insurance market. So the risk profile is starting to go up for a lot of these projects.”

Battery cover

McLachlan says GCube “likes batteries” as an asset class, despite having been burned in the past – literally.

“Battery storage was one of the biggest claims we ever paid – a $34m claim – from a storage system that went on fire. So we learned pretty quickly,” says McLachlan.

“But rather than run for the hills, we learnt a lot. We like batteries. Those sorts of storage solutions are where the industry is heading.”

The fire risk from batteries “is not as benign as some may think”, says McLachlan. “So you have to be careful about the people that you are working with and there has to be proper due diligence on some of the newer players coming to market.”

Outside of fire risk, “it is pretty benign technology”, says McLachlan. In terms of insuring storage against lost revenue, “the only other thing is trying to quantify the quantum of the loss in terms of the amount of power that would have been generated by the battery storage facility at the time it broke down”, he says.

“That is the challenge – do you get paid for 20 calls [from the grid operator to provide services] or twice?”

Cutting costs, transferring risk

GCube provides the following example of how solar developers are reacting to squeezed, post-subsidy margins:

With subsidy support, a project was able to configure a substation with dual transformers with a 70% capacity factor on each. The cost was an additional £4m to construct.

Conversely, a recent project ‘built to price’, had a single point transformer, such that if it failed the project would be offline for at least 12 months. This project saved £2.2m by doing this. Insurers took on the added risk but increased the underlying premium by 20%, so the rate went from 0.2% of capex and an annual premium of £340,000 to £408,000.

This article was originally published in the December/January print edition of The Energyst. If you are involved in energy within your organisation, you may qualify for a free subscription.

Related stories:

Free battery storage report (incl solar and storage)

National Grid to bring wind and solar into frequency response

Nottingham City Council: Solar ‘absolutely still viable’, batteries next

BP takes big stake in Lightsource

Next Energy snaps up two more solar farms

Small is beautiful, says UK’s largest solar fund

Next Energy buys 22MW of solar farms

BP takes big stake in Lightsource

Solar and storage must bow to grid king

Kiwi Power to build 4MW behind meter battery in south Wales

Anesco builds ‘subsidy free’ solar and storage farm

Solar farms with batteries can keep earning Rocs

As solar subsidies wane, investors plan 2.3GW of battery storage projects

17% of UK solar capacity ‘to be sold within 12-18 months’

Sheffield University launches three day solar forecasting tool

Big fish: BlackRock and Lightsource target £1bn solar portfolio

As solar generation makes history, National Grid starts to feel the burn

Solar PV hits 12GW, further 3GW in planning

United Utilities plans £55m solar investment

National Grid procures 138.6MW of demand turn up to balance solar in summer

National Grid to extend demand turn-up running hours, procure more

National Grid says impact of solar requires greater system flexibility

Click here to see if you qualify for a free subscription to the print magazine, or to renew.

Follow us at @EnergystMedia. For regular bulletins, sign up for the free newsletter.